The New Western And Self-Flagellation

(leer en español)

Towards An Analysis Of The Frontier’s Hero’s Reinvention

The Last of Us Part II ends with a sequence that flirts with horror and is, like many other sequences in the game, unapologetically morbid. Ellie, the main character whose growth we’ve witnessed since she was thirteen years old in The Last Of Us—and by the way, one could make a case that this Ellie is a different character altogether from that other one, with very few things in common—, finds Abby, her enemy, and forces her to fight to the death by threatening to slit her adopted sibling’s throat. The fight between Ellie and Abby is a long sequence of hard hits, stabs, and any number of vicious attacks between them that turn the water in which they’re fighting red. In a particularly brutal moment, Abby bites Ellie’s hand, plucking away a couple of phalanxes from her fingers. The fight does not end in death for any of the main characters because in a sudden moment of lucidity—that took hundreds of cruel and bloody murders until finally arriving—Ellie remembers Joel and, honoring his memory, decides to let Abby go.

Having survived her insatiable thirst for vengeance, Ellie makes her way back home only to find it completely empty, except for her personal items packed up for her in what used to be her room. Among them, it’s her guitar.

By the time we reach this scene, we’ve seen Ellie sing and play the guitar several times already, in what was the only means for her to channel her last drops of humanity. Now, having partially lost two fingers, she’s no longer capable of doing so. The result of our hero’s journey is not death, but something that seems even worse: the absolute loss of that which reminded her of humankind.

The Last Of Us Part II, just like the first part, takes place in a world where there’s no artistic or cultural production whatsoever. The cultural items the characters find along their way, either comic books, DVDs, or books, are all dated 2013 or before, the year in which the apocalypse took place in the game. The video game consoles are all PS3 or Vita. The songs are always from 2013 or before as well. In that sense, playing said songs on the guitar is undeniably an attempt at belonging to a humankind that no longer exists. By the end of The Last Of Us Part II, Ellie can no longer hold to that.

The question that Ellie does not ask herself nearly often enough, if at all, is why her journey takes her in that particular direction. Because—and this is clear for every player of the game, and probably partly responsible for some of the harsh reception that the game had—everything that happens to Ellie is her responsibility.

On one part, her main motivation is clear and organic. In the game’s world, we don’t need any explanations or justification to know that, if someone murders Joel, Ellie will find them and make them pay. But that fact, which could be enough to build a perfectly complete and conclusive plot, is not enough to turn Ellie into a cruel murderer machine. Instead, the driving force for Ellie is a more visceral, basic one: guilt.

As she sang during the trailer released in 2016:

No, I can’t walk on the path of the right because I’m wrong.

Ellie’s guilt has at least two different, big reasons. On one hand, not having stopped Joel’s murder or, perhaps even worse, not having fully fixed her relationship with him before his death. And secondly, on a more general level, she suffers from essential, not redeemable guilt from not having saved mankind when she had the chance to do it years ago. With this feeling of guilt and constant regret, she lets herself fall into a destructive spiral that only worsens it. To her two big reasons, throughout the game hundreds and hundreds are added in the countless murders and atrocities she commits.

Two years before The Last Of Us Part II launched, another sequel to an equally paradigmatic game had been released, Red Dead Redemption 2. Like Ellie, this time Arthur Morgan is presented as our tortured hero: with a past mostly unknown to us, Arthur evokes a permanent feeling of regret for the things he’s done.

On more than one occasion he talks about having been a “bad man”, and in one particular dialogue he gives some detail on what he means:

I’ve been killing… a lot, I mean, innocent folk. I don’t know why.

Also like Ellie, Arthur wanders through a world beyond the frontier and away from his culture, and the hostility and lack of humanity of his environment reflect accurately the ethic and moral desert of the character.

This narrative device, embodied in the very idea of the frontier story—in The Last Of Us Part II, the frontier is everything outside of Jackson, Wyoming, while in Red Dead Redemption 2 the frontier is constantly escaping the characters to the west—, is nothing short of a confirmation that these are two pieces that work within the Western genre.

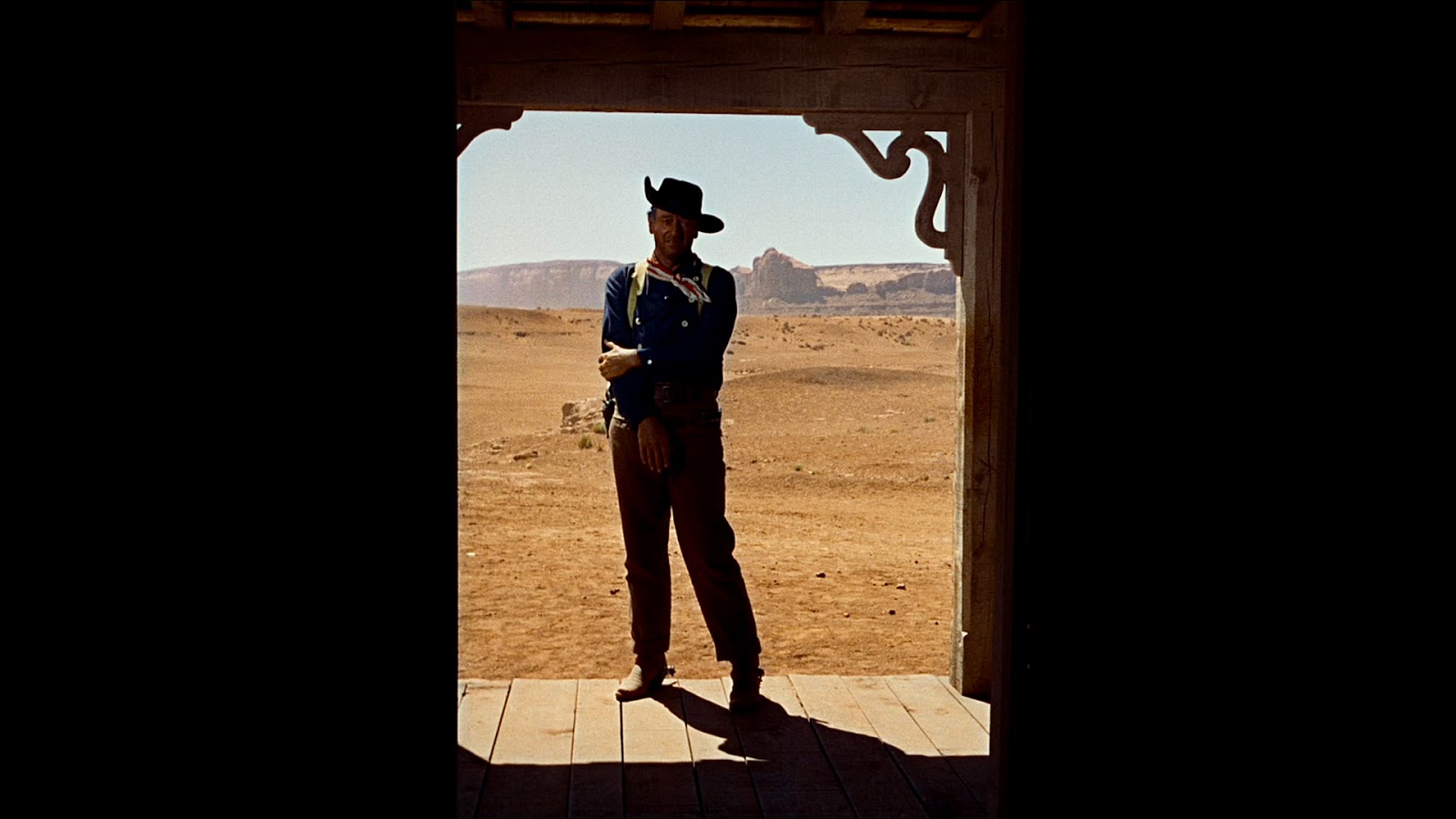

In what is probably the most paradigmatic Western film, The Searchers (1958), one of the main characters is also portrayed as a product of his surroundings. Ethan Edwards, played by the endless John Wayne, belongs to the desert more than civilization. The most emblematic shot of the film, and one of the more expressive shots in film history, shows him standing on the threshold of Laurie Jorgensen’s house, in between both of his worlds.

Even after the adventure that took him out to the wilderness in the search for Debbie for years, Ethan cannot enter the house that he was once a part of (however briefly).

Ethan belongs to the outside. A son of the desert, in the fight between civilization and barbarism that take place within him there is no clear winner. His hate toward the Comanche people, even if born from personal experience, is extreme, racist, and irrational. He goes as far as shooting a dead Comanche in the eyes to stop him from reaching heaven according to his people’s beliefs. This character is the hero and the villain at the same time, part of the American culture but a horror and a menace to it: he goes to search for Debbie all right, but instead of saving her, he plans to kill her for having joined the enemy.

We can maybe, then, think of a triad of frontier antiheroes. Ethan, Ellie, and Arthur live halfway between society and savagery, safety and extreme violence. But there’s a fundamental difference, that I consider the main rewrite of this genre’s character: Ethan doesn’t feel guilt. He might think twice, and he might even change his mind (after all, he ends up not killing Debbie, but bringing her back home instead), but he’s not constantly tortured by his own acts, and certainly does not make it worse as he attempts redemption.

Ethan knows that he cannot fully go back to society (as Ellie and Arthur do), but he’s at peace with that fact. Arthur can’t stop thinking about the bad he’s done, and his attempts to amend it are useless and mild. Ellie, on the other side, is barely able to process the guilt, and the only thing she can do with it is to punish herself relentlessly. Facing the reality that she’s done horrible things, her response is the appropriation of that morally negative identity. That is, faced with the possibility of being a monster, Ellie decides to turn into one.

There’s no attempt at redemption in Ellie, and even less at acceptance or forgiveness. She’s so aware of her own guilt and character that she can’t do anything but stare at herself in the mirror as a horrible being, and affirm it time and time again. The result, then, is not surprising: there’s no possible reflection or conclusion for the character. She’s freed from any responsibility and any form of redemption—in the same way, perhaps, that the authors are freed from dealing with her. That’s where the sense of emptiness and superficiality comes from in The Last Of Us Part II: there’s nothing to be said about Ellie, just as she doesn’t have anything to say or think about herself except for the affirmation of her newly found identity as a monster. In her irrational, antidramatic atrocities rally—there’s no narrative structure, no character growth, only accumulation—the story dies in the same way that culture has died in the world the character lives in.

Where Ethan understands his place in society and the theater of the world, Ellie and Arthur can’t stop thinking about themselves. Hence, the Western trope of the external desert as a reflection of the internal one finds a new expression, in which the characters are unable to even see the desert to start with. I wouldn’t be as bold as to see a tendency based on only two works (even though they’re probably the biggest video games of the last couple of years), but I can at least point out the elements that stand out both for their appropriation and rewriting of the genre. Maybe we are, today, discovering a new paradigm: that of the self-centered antihero.