Kishōtenketsu, The Four-Act Structure

(leer en español)

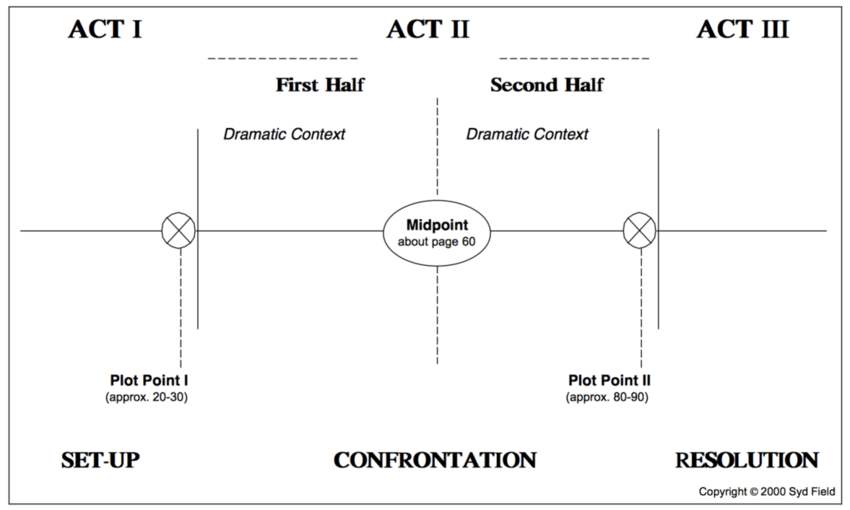

Lately I’ve been completely immersed in the so-called classic story structure in screenwriting and narrative: the three-act structure. Attributed to Aristotle based on his principle of stories having a beginning, middle, and end, this structure was actually popularized by Syd Field in 1979 through his book Screenplay, in which he also introduces the concept of plot points, basic to the now “classic” concept of narrative structures.

The Western version of narrative classicism is based on this idea of three acts (there are several practical analyses of this idea in this very blog) or, in any case, the pre-Fieldian idea of the five acts (see John Yorke). This post is not meant to get into any of these, but to research one of the many other narrative structures that, even if sometimes is not apparent, do exist.

McKee mentions the concepts of Miniplot and Antiplot in his immensely popular book, in what is a refreshing outlet from the ideas of three acts and plot points as the fundamental and necessary plot elements. For a while, I believed that those two were the only alternatives to what I always knew as the classic story structure, but the reality is much more complex than that.

Within said complexity, a while ago I stumbled upon an analysis model that I’d never heard of before. Kishōtenketsu (起承転結) is a narrative structure based not on three or five acts, but on four, originated in China with the name of qǐ chéng zhuǎn hé (起承轉合) and made mainstream in Japan with the aforementioned name. Beyond the number of acts—which could be a structural thing or, just as well, an arbitrary decision—what piqued my curiosity in preliminary research of this structure was that it didn’t apparently involve a notion of conflict, or at least not one as clear as the one that forms the basis of our Western classic structure.

The premise is interesting, particularly when taking into account that kishōtenketsu is supposedly the narrative modus operandi of Japanese commercial productions in manga, anime, and film. A commercial-viable structure without a clear idea of conflict made me think, at the very least, of a translation problem regarding the concept of conflict. And maybe there is some truth to this. The problem is that, as with many things related to East Asia, this structure comes to us in quite an obscure way, and there are not many accessible and/or serious studies on the subject. I will try to surpass this obstacle anyway, and attempt to understand what kishōtenketsu really is about with the scarce sources I have at my disposal.

Speaking of sources, there are plenty of blog posts around that explain this structure in a very basic way; most of them repeat more or less the same, and finding the origin of this army of clones is not an easy task. An exception to this, however, is a long post by Kim Yoon Mi, a Korean author and scholar, in which she analyzes non-Western narrative structures and includes the one that concerns us. Even though the author is a little bit aggressive with the Fieldian/Aristotelic model—on reasonable grounds—there’s plenty of valuable information in the post: not only the mention of dozens of narrative structures and a clear analysis of kishōtenketsu, but also the link to an interesting source, which is a series of three videos by Japanese mangakas who explain this structure.

These videos are, for their origin, their case studies, and their relative extension, the most reliable source to study this subject that I’ve found as of writing this piece.

Getting to the point, then, what is kishōtenketsu? The structure originates in classic Chinese poetry and, as the mangakas say—this last confirmed as well by my Japanese-culture expert of choice, Eduardo López Herrero—is omnipresent in Japan, used in as diverse media and storytelling devices as children’s stories, serial mangas, Kurosawa films, and even PowerPoint presentations.

The four parts that shape the structure are:

- Ki 起: Introduction

- Shō 承: Development

- Ten 転: Twist

- Ketsu 結: Conclusion

The four parts seem pretty clear and easy to understand, and if we were to remove the third point, we would be left with something very similar to beginning, middle, and end, the old Aristotelic definition. This alone should give us a hint about what is the key element of this Japanese structure.

Now, even with the presence of the third part, it is very tempting to think about our three-act structure and verify if, actually, this is not simply a different interpretation of the same core structural outline. Within the Western-dominating Fieldian paradigm, we can find what is called a midpoint, a structural point of variable value depending on the author. Sometimes, it is barely mentioned as a structural point, but often it is considered a turning point within the second act, making it almost as important as the plot points that separate and define the three acts. In this paradigm, the midpoint breaks the second act in two, ending the protagonist’s Plan A and giving way to their Plan B. It may seem, then, that this idea turns the three-act structure into basically a four-act one. Is this what the four-act Japanese structure is about?

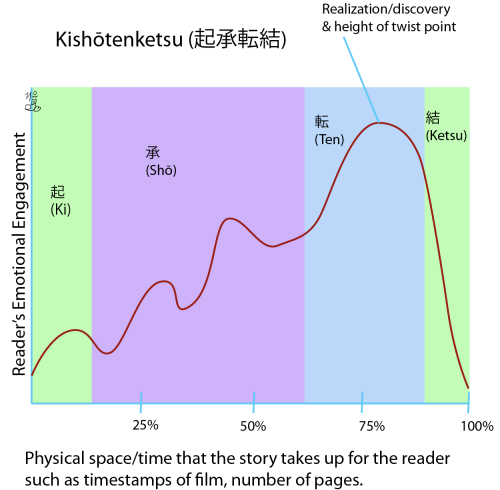

The answer is no, but this is not as easy to see. In the diagram presented by the cited mangakas, it is clear that things are not that simple:

(diagram by Kim Yoon Mi)

For starters, if Ki and Ketsu were the first and third acts, they would be extremely short in terms of duration. Besides, their dramatic weight is clearly not the same. This is particularly evident with a quick look at Ketsu and the Reader’s Emotional Engagement curve on it: far from being the place where the climax takes place, as in the Fieldian third act, Ketsu is the place where the reader’s attention and the plot tension go flat. This means that this is not, by any means, another lecture on the three acts, as much as the translation of the terms may point us in this direction.

The variable Reader’s Emotional Engagement, though, might give us the second key to this structure. According to this idea, kishōtenketsu is not defined by the plot events in the way the Western structure is, but instead by the effect of said events on the reader/audience. That effect, distributed throughout the story, creates the pace of the structure. Where Field puts characters and plot as the defining elements, kishōtenketsu puts audience and pace.

Taking this into account, the main point of the structure—Ten, the twist—only works in relation to the audience’s expectations, and its role is to defy them. The twist is based on the unexpected.

This short and initial study leads me to conclude that kishōtenketsu is not only a different narrative structure, but more than that, a different story building and interpretation paradigm. This paradigm doesn’t observe the same elements that the Western paradigm does in a different way; instead, it observes entirely different elements altogether.

A case study: Jujutsu Kaisen

The only way to try and understand how all this applies to the real world is to see kishōtenketsu in action. At some point, I’m interested in taking a close look at this in relation to a film by Akira Kurosawa, since he allegedly claimed that all his films followed this structure. For now, I’m happy to analyze the first episode of one of the most successful anime series of the last years, Jujutsu Kaisen.

In the episode, apart from the hook—which would be the strange dream-like sequence at the very beginning—we can consider the first two scenes right after that as the introduction set. On one of those, we meet Itadori and become aware of his immediate conflict: his grandfather is dying at the hospital, and yet he insists on Itadori attending a club. Right after that, we meet Megumi Fushiguro, who’s looking for a cursed talisman on high school grounds, and is alarmed when he finds that the talisman is not where it’s supposed to be. In short, we get introduced to the main character in one scene, and to the main plot device (the curse) in the other. As a Ki segment, which is supposed to take roughly 10-15% of the length of the story, this seems to make sense.

Next, we move on to the Shō, or development segment of the episode. This is the longest one and where the main story conflict emerges. Among a couple of subplot scenes, the most important point is Fushiguro asking Itadori—we know by now that he’s in the occultism club—about the talisman, and warning him that were the talisman to be opened, a catastrophic event would happen. The two worlds clash in this scene: the cursed talisman meets Itadori and his friends, and the expectations are set in that the talisman cannot be removed from its wrapping. This happens around 14 minutes into the episode, which is about 60% of the story, in line with the structure presented on the diagram.

The expectations—Itadori and Fushiguro retrieving the talisman from Itadori’s friends and stopping the calamity—are quickly subverted when the talisman is released and mayhem ensues. During the Ten segment, Itadori fights against the demons alongside Fushiguro and beats them to save their friends, giving place to Ketsu not at the actual ending of the episode (during the last 10% that would be consistent with the structure), but a little bit before, around minute 19. There’s calm after the fight in which Itadori’s motivations and growth are shown. The tension is gone, and a new balance is found.

Almost as an epilogue, during Ketsu, a new warning is announced: if the finger, the core of the talisman, is swallowed, the person who swallows it would gain immense strength, but they would be cursed in return. This sets up the final sequence that makes up the cliffhanger which, according to this analysis, wouldn’t be a part of the proper structure of the episode.

In any case, this epilogue sequence shows a micro version of what the core mechanic of kishōtenketsu is: setting up expectations to then act on them. It is certainly not conflict-less, and is probably compatible with a three-act, if not conception, at least interpretation of the same plot. What it is, more than anything else, is a different perspective on how to think about story.